My First National Geographic Assignment on an Antarctic Volcano

How learning to tell a story transformed my photo career.

When I graduated from art school with a degree in photography in 2014, I was clueless about how to make it a career. While my classmates all moved to New York City with dreams of making it big in the art world, I decided to go as far from the art world as possible, and got a job as a photography guide on ships in the Arctic and Antarctica. Instead of struggling to survive in a big city, I traveled all year to places that interested me, and photographed my own work on the side. I didn’t really know how photos got published in magazines, but I worked on personal projects at every chance I got, and dreamed that one day, I might figure it out.

Then, in 2017, I was packing my bags for my third season in Antarctica when I got an unexpected email from a photo editor at National Geographic, asking if I had any ideas for a story I could work on while I was there.

The word “story” glowed ominously from my laptop screen. In art school, I had learned how to create a cohesive series of images that might work in a gallery show or a photobook. But as a naïve student, I had stubbornly resisted the idea of intentionally, literally telling stories with pictures. Documenting the facts of the world sounded like a recipe for all that was dry and boring—certainly not terrain for a dreaming artist, like me. Now, though, my work took me to places where the real world was more visually fantastic, and certainly felt more important, than anything I could invent.

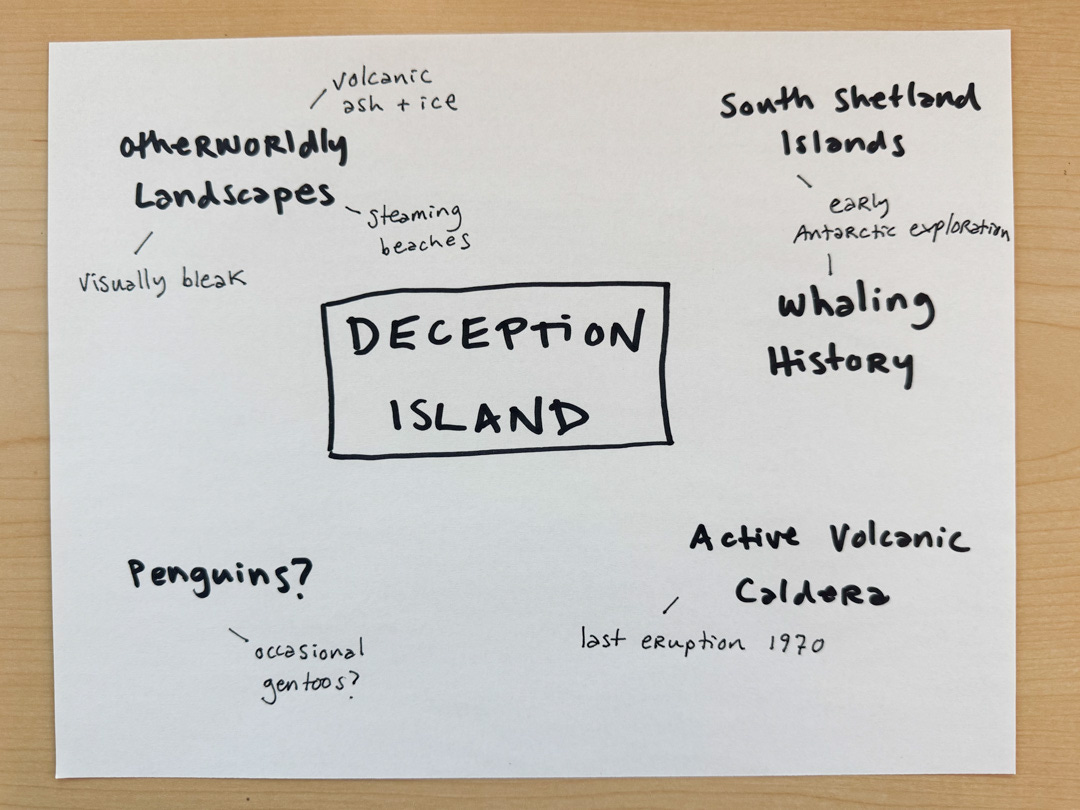

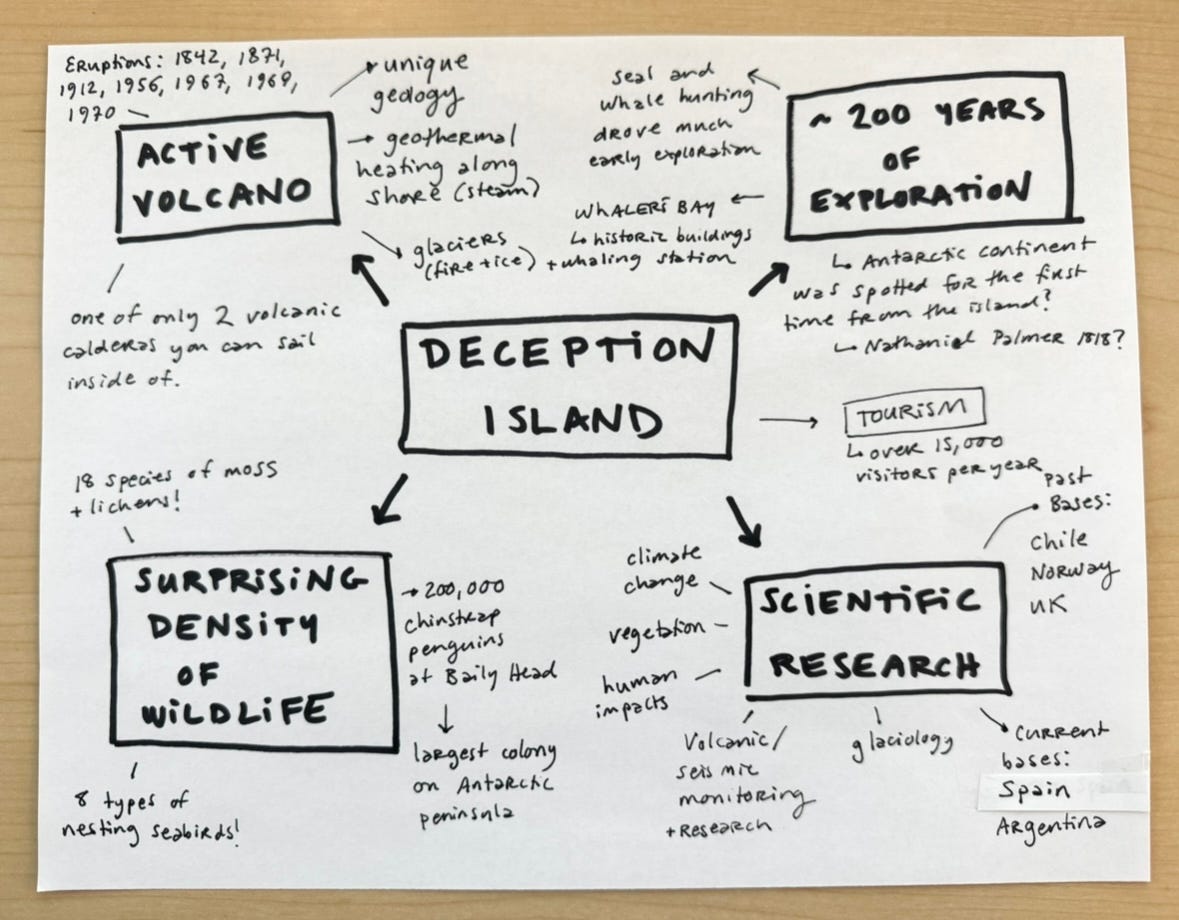

With National Geographic on the line, I feverishly brainstormed a list of my best story ideas, eager to find something, anything, that might work. But when I read them aloud to my family to test their viability, I saw that none of them were really stories at all. They were topics – and learning to turn them into stories would change my career.

The most useful thing I did learn in art school, it’s worth mentioning, was the value of a cohesive series of photographs. Whether we like it or not, the enduring places where photographs are displayed, published, and paid for—galleries, books, magazines, newspapers, even some brand campaigns—all favor a series of photos that fit together as a group. In the art world, images can be imaginatively connected around a concept or theme, but in magazines and newspapers, the images typically must work together to tell a true story. This felt a lot harder, like something I wasn’t sure I felt qualified to do, and thus, I had never really dared to try it.

(For example, “Antarctic Penguins,” might sound like a great topic for a photo series, but it is tremendously vague. Unless there is a specific narrative arc or the photos are exceptional in some way, it is unlikely to be urgent or newsworthy enough for a magazine headline. How about “As Antarctic ice melts, emperor penguins march towards extinction”? The specificity, context, and urgency all make this a solid National Geographic story, but as you’ll discover if you read the piece above, it took photographer Stefan Christmann two six-month winters with the penguins to pull off.)

At age 27, guiding a group of 200 tourists, with no particular wildlife access or free time outside of an established tourist track, my options in Antarctica were limited. The idea the editor eventually approved was about Deception Island, an active volcanic caldera in the South Shetland Islands with a former history as a whaling base, which I was confident I would visit several times that season. It wasn’t exactly a formal assignment, but it was an opportunity to prove myself, a challenge I took on with an almost hilarious degree of intensity.

When our ship sailed inside the eerie, ash-swept interior of the Deception Island caldera a month later, though, it was so windy that it was impossible to go ashore. On our second visit, seduced by the glamorous idea of “doing anything for the shot,” I drowned one of my two cameras in the pouring rain while photographing an abandoned whaling station. (The shots, in an unseasonable Antarctic downpour, were not very good). There was no wildlife to be seen, except one forlorn penguin carcass, and my photos were quickly becoming an abstract, rain-misted study of ash, ice, and volcanic ruin.

For the story to have any sort of narrative tension, it needed a contrast to this monochrome bleakness. By some miracle, conditions were calm enough on our third visit to go ashore at Baily Head, a chinstrap penguin colony on the exposed rim of the caldera where breaking waves often make the beach too dangerous to land on. By another miracle, my expedition leader allowed me to sneak away from our group of 200 guests for a few hours onshore.

Between the crashing waves of the black-sand beach and a verdant, moss-covered amphitheater, a superhighway of penguins moved back and forth between their nests. Over 100,000 pairs of birds, their fuzzy grey chicks just recently hatched, nested on the volcanic slopes. It was a cacophony of life, noise, and scent—a stark contrast to the desolate landscapes of the caldera’s interior, and the very thing the story needed to come to life.

The piece was eventually titled “Wildlife is Thriving on this Eerie Polar Volcano,” and while the visual story barely held together (and needed 100 years of historical imagery to feel complete), it was the first of several steps towards my accidental journey as a wildlife photographer, which believe it or not, I had never directly aspired to be. More importantly, it marked a pivotal shift in my thinking about what makes a photo story successful, which has opened doors for me professionally ever since.

Now, every time I have an idea for a photo project I want to pitch to an editorial publication, I pause and ask myself: is this actually a story, or do I just want it to be one? This is the first step towards deciding whether a project idea is going to be a fit for a magazine, and it still amazes me how often that initial flash of inspiration reveals itself to be wishful thinking, caught up not in a clear narrative arc but in a visual dream of how beautiful the photos could be.

Now, after over ten stories for National Geographic and many more for other outlets, I have learned to create story maps whenever I begin to plan a new project, starting with the who, what, when, where, and why. This reveals three essential things:

Whether the narrative is robust enough to warrant a full article

Whether it is logistically feasible within a set timeframe and budget

Whether all the facets of the story can actually be communicated through photographs

And yes, this all requires research.

Now, my younger artist self would probably have balked at this structure. But the reality is that in a magazine, we’re going to end up with around 8-14 final images to introduce a story’s context, characters, the “plot,” and the questions, discoveries, or emotions it aims to raise. Keeping the story outline in the back of my mind ensures that nothing important gets forgotten—and far from being constraining, I’ve found that a structure often opens up new creative directions to intuitively explore.

Sometimes, the photo project I most want to pursue is simply not an editorial story, and that is okay. (I will always love the art world of my origins.) But when I look back at my youthful resistance to storytelling, I suspect it was because I knew that it would demand more of me—or at least, a different side of me—than my fine-art photography did at that time. Learning to tell stories has transformed photography into something I can actually be hired to do, opening up a world of professional opportunities in my life and in the lives of other photographers I know. So far, it has been worth the challenge.

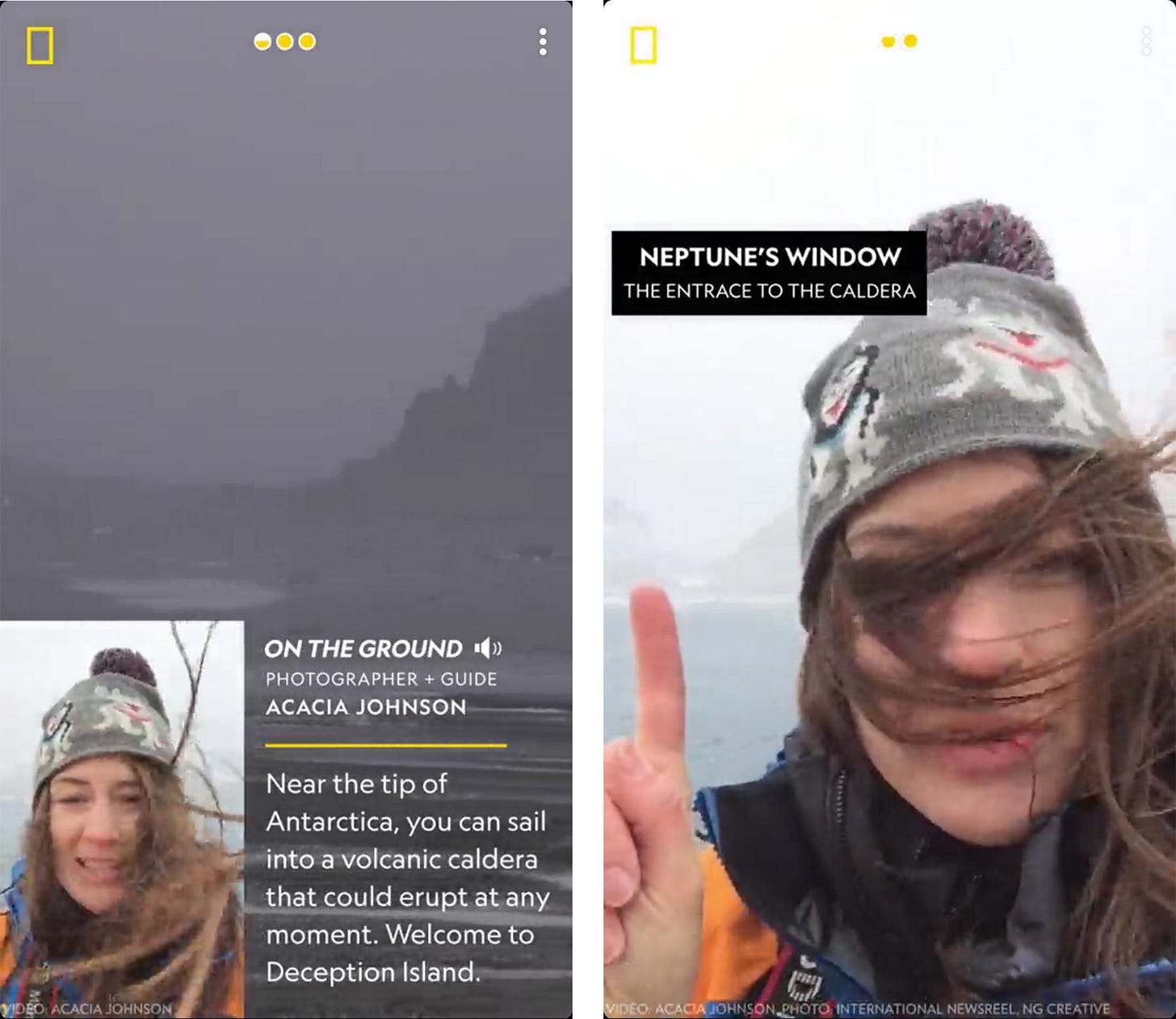

Oh, the Deception Island piece? It was released alongside a brief, windy social media story, complete with selfie video and waddling penguins, published on International Women’s Day… on Snapchat. I burned up my meager shipboard allowance of satellite internet to watch it, pixelated and all, before the story’s 24 hours were up and it disappeared into the ether of the Internet past. A new chapter in my journey as a photographer had begun, and I’ll always be grateful to the editor who first gave me—and my first story idea—a chance.

What I’m Looking At: I recently re-discovered Evgenia Arbugaeva’s series Weather Man while researching stories for an upcoming post. This magical little story about a meteorologist at the end of the world is the first chapter of her book, Hyperborea, which came out last year.

What I’m Reading: The Sea Around Us by Rachel Carson. Good lord, what a masterpiece of poetic and informative literature. I love intense nature writing and this one literally makes me laugh with joy at how beautifully it is written.

A Photo Resource: As we recover from this season of buying and gifting, it feels like an opportune time to point out some great resources for secondhand camera equipment: the B&H Used Department and KEH Pre-Owned Camera Gear. The cost of photo gear can be a huge hurdle to photographers starting out, and some of my favorite cameras and lenses are ones I purchased secondhand, at a fraction of the price of what it would have cost new. (They are also in beautiful condition and will likely last for the rest of my life.)

Thanks for reading, everyone! This piece was a response to a reader question. I’d love to hear your thoughts on this piece and what you’d like to read next.

This post is public, so please feel free to share and spread the word. Until next time!

Useful and inspiring for those of us who enjoy trips for the feelings and stories (just back from South Georgia) and when we return home, pick up a pen and start flowing about the experience. I’ve been considering structure and found your post tonight. Many thanks

You have my “Once upon a time” dream job.